This is the first in a new series of conversations around the theme of Contemporary Communitarianism. For this issue, STIR’s editor Jonny Gordon-Farleigh speaks to writer and civic advocate Pete Davis about why the decline of local clubs and associations represents a crisis of democracy and what can be done to transform a "gaseous" society into a culture of solidarity.

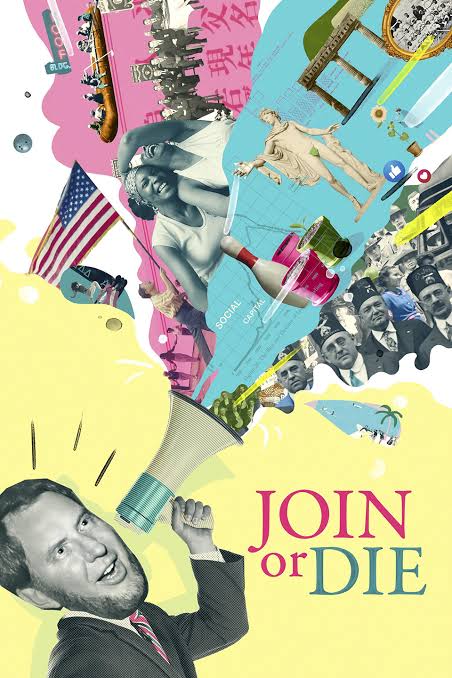

JGF: You’ve recently co-directed a documentary production – Join or Die – about the unravelling of civic life in the US since the post-war era. Building on the work of Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone, the film argues this decline in civic membership has undermined democracy and community life at all levels in modern society.

What gives you cause for optimism that joining a local club or national association can start a process of democratic renewal?

PD: We know from Robert Putnam's work – Making Democracy Work and the best-selling Bowling Alone – that social participation in civic groups is connected to flourishing across all institutions. When a place has more clubs, civic associations, and local newspapers, more neighbours know each other, and there is more participation in public life, and they have better government, health outcomes, and education. It is correlated with more thriving economies, and more equal economies. And you can think about the causal mechanisms – how we get things done when we come together with other people, when we have higher trust in other people, how more good ideas spread; more institutions are watchdogged because more people care about them; and more people want to participate not only in making things happen, but also in stewarding things. For instance, they not only do a park clean-up, but they also want to throw away their trash because they know their neighbours, and they feel part of something bigger than themselves.

What's great about local clubs is they actually get you out there doing the real work. And historically this is the case, too: behind every social movement in the United States, there are usually people meeting regularly in some organisation that is making something happen. If you look behind the abolitionist movement, there are newspapers like The Liberator and groups like the Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Sewing Society. It was churches, labour unions, and student groups that led to the civil rights movement. And in the gay rights movement, there was a major group called ACT UP (or the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) in the 1980s and 1990s. The famous Margaret Mead quote – “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has”” – is very true.

There is quite a large taxonomy of associations in the US and Europe, ranging from leagues, fraternities, and societies, to unions and federations. Can you talk about the nature and structure of these associations in US history?

When we made Join or Die, we used the term ‘club’ in the broadest sense, meaning any type of association where people are coming together to get something done. They range from what we sometimes refer to as ‘light’ or ‘soft’ clubs, such as cooking clubs, knitting clubs, and sports leagues, all the way to the more hardcore, political clubs, such as political parties or social movement organisations like Students for a Democratic Society; the NAACP (the National Association of Colored People), which is a huge part of racial justice in our country; or the Women's Christian Temperance Union, which was a huge advocacy group for the suffrage movement in the United States. And then everything in between, from congregations to unions to professional associations to guilds, which, from the early 1800s, were effectively artisan clubs. There is also a huge culture of what are called fraternal organisations, which are groups focused on building fraternity, while also providing service and moral development. The most historic one is the Freemasons, but then came the Oddfellows. And then we had a string of the ‘animal clubs’: The Elks and The Moose, The Lions and The Eagles, many of which peaked in the mid-twentieth century. Then we had popular federated service clubs that have gone international: the Rotary clubs, the Kiwanis club, and others of all flavours, from rural clubs like the 4H and urban clubs like the Urban League.

There's an impulse to talk about the nuanced specifics of all these clubs, but one of the things we're trying to point out in Join or Die is what these clubs have in common. Most notably, the civic skills you learn in any of these clubs are transferable to other contexts. So what you find in American history is that someone might learn how to co-operate in a church, and then use that skill in their fraternal organisation. And then that fraternal organisation starts an insurance co-operative. Or eventually, a labour union organiser becomes a civil rights organiser, or a person who learnt how to preach in churches, like Martin Luther King, learns how to preach on the National Mall for a big national change event. Or a club member might eventually run for office. The skills we learn in any part of civic life are transferable to other parts of it.

In the current moment, the nature of association, as political theorists like Anton Jäger have put it, is more “gaseous” and the expectation of affiliation to certain causes is much looser and cheaper. How do you think about the question of ‘entry’ and ‘exit’ for both individuals and organisations?

Zygmunt Bauman is one of my guides on this. He writes about ‘liquid modernity’, where he argues the world has become liquid: we don't become particularly connected to anything so we can adapt to any future circumstance, and our organisations aren't committed to us so that they can adapt to any future circumstance. The best book on this in the American context is Theda Skocpol's book Diminished Democracy: From Membership to Management in American Civic Life (2003). We still have a civic life in America, but the groups representing civic life look very different than they did 75 years ago. Then, civic life was mass membership organisations where you were meeting in local chapters. In this context, to be a member of the organisation meant you met with other members, and it was literally embodied in your town through meetings. Those meetings federated up to become mass membership organisations through local chapters, regional chapters, state chapters, and eventually national chapters. Real local membership translated into national action.

But then, in the second half of the twentieth century, we traded mass membership for centralised management. We said, ‘Oh, all these local chapters, we don't really need them.’ We can just turn them into a mailing list, they can send us cheques, and that can pay our lobbyists in Washington, who can get a lot more done. We’re the experts in advocacy, and we can just send an annual report at the end of the year to our “membership” and tell them we've spent their cheques well. And maybe we can mobilise them once a year to vote in an election or write a letter to a congressman. But what happens is that the Sierra Club or the American Civil Liberties Union become something that you write a cheque to and are ‘managed’ by: they're trying to get you angry about the latest attack on your cause. So you write a $50 cheque so centralised actors can do more things. But the anger button eventually gets fried and the cheques don't even start coming anymore. The amount of mobilisation doesn't happen anymore. People get really cynical about politics. That, I think, is what you might be getting at with this idea of “gaseous organisations”.

Those meetings federated up to become mass membership organisations through local chapters, regional chapters, state chapters, and eventually national chapters. Real local membership translated into national action.

Then with the internet, this is hypercharged with the fake mobilisation of liking a post or retweeting, or a quick donation drive where you can click a button. This makes everyone feel like they're doing all this action. But none of the congresspeople, the big corporations, or the big power players are actually scared because it doesn't add up to much. When you have a mass membership organisation, you can wield actual power. And so if we really want to build power again, we have to rejuvenate mass membership organisations.

Through your work at the Democracy Policy Network, you’ve recently focused on ‘cultivating civic membership’. This is about creating a membership culture between residents in towns and cities in the US in an era when such ‘associational bonds’ have weakened as municipal leadership has become more technocratic.

Can you relay this history of civic membership in US history and outline some of the approaches and policy demands you include in your new toolkit?

In his studies, Robert Putnam presents all of these very particular ways we're becoming disconnected: you participate less in clubs, you attend meetings less, you read the newspaper less, you know your neighbours less. One of the things we're trying to get at with the idea of city membership is that all of this adds up to something bigger than the sum of its parts – a feeling that you are a member of your town. Being part of the Rotary Club or knowing your neighbours or going to school board meetings adds up to a sense of being part of a town, or a neighbourhood, or a city, and taking both pride in it and responsibility for it. So participating in a local club is not just about the club; it's about the town as a whole.

When being part of a town just means renting or buying a property in a geographic spatial location, you’re part of a space, not a place, surrounded by strangers, not neighbours. The government is not something that you’re a part of; it’s the thing that gives you parking tickets and collects taxes. There may be vague things called ‘volunteer opportunities’, which you might do one Saturday a year, but it’s seen as an individual pursuit. There's not a sense that you’re part of this shared project called The Town. And this is a huge part of American history. There's a whole culture in big cities around neighbourhood pride. And then in the heartland of America, there are all these stories in American culture of local town pride, and there are hundreds of movies about a town coming together to achieve something. In the 1946 movie, It's a Wonderful Life, there’s a famous scene where an entire town helps one of the characters.

One of the things we're pushing with the Democracy Policy Network is to ask, ‘How can we rekindle a sense of city membership, neighbourhood membership, or town membership?’ In addition to rebuilding associational life generally, we have some particular ideas about this. Towns, neighbourhoods, or cities should see themselves as a platform for all of the civic life in the town. So they should run a civic census of all the civic groups in town. They should publish that in a civic directory. There should be responsibility for the proliferation of meeting spaces in the town. The government should see itself not as just an arbiter of bureaucratic processes, but as a site of citizen participation. We even have a proposal that makes the case for assigning everyone a neighbourhood block captain in a town, to make the challenge of building neighbourhood cultures more accessible. It gives a permission structure for someone to go around and say, ‘I'm your neighbourhood block captain, and we're throwing a block party, or having a neighbourhood discussion’.

Another set of ideas is based around having a culture of welcoming when someone moves to a town. It's not just that you made a real estate transaction when you moved to a town. You are being welcomed as a member of this town by giving you a welcome kit that tells you about the town, and offers welcoming liaisons. What this all adds up to is the sense that a town should not just be thinking about their economic development; they should also be thinking seriously about their civic development.

One seminal text on Atlantic communitarian history and its relationship to national social policy is Daniel T Roger’s 1998 Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age. One of the real challenges it presents for civil society is how it can become overdivided along sectarian lines. For example, the main issue for the US in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is not a lack of associations and societies, but their inability to build strong coalitions that can secure social policy at the national level.

In terms of contemporary communitarianism in the US, how much is this still a problem, and how can we potentially build stronger coalitions?

This is a very important question. One of the most evil clubs in American history – the Ku Klux Klan – terrorised communities for a century, and they peaked at the times when we had the most active civic life. We do not only need clubs that bond us to people that are similar to us; we need clubs that bridge us across divides. We need to be thinking about where there are points of segregation in a society and think about what clubs and institutions can bridge those.

In America, for example, the military has done a lot of work in bridging across divides. It takes people from all across the country, across all races, and actually helps bridge some divides. Religion has been a way that has bridged some economic divides, too. And so we need to think about that when there are divides across generations, race, class, and political belief. We need to think about strengthening those institutions and clubs that bridge divides in society. That's easier said than done, but the work is very important.

In terms of building a national coalition, a bunch of nice little civic clubs in all the towns does not make a national programme. Just because you have rotary clubs everywhere does not mean you're going to translate that into national power. That is where coalitions come into play. And the way I just see this, structurally, is that communities are the base level of organising – they're the tiny building blocks that bring people together in the first place. That right now, as we've been talking about, is very weak. And so what we need to do is to cultivate all these little communities to just get us from a totally individualist society to having any collective sense of community at all. But community is not enough.

We also need coalitions: collections of communities that come together to secure change at the national level. And there are three entities that do this. One is federated organisations. As Skocpol discusses, we need more than just a bunch of ad hoc civic groups in every town. We need organisations that federate us into state and national and international projects so that they can act at those different scales.

The second type of group that brings people together is social movements. We need to put together social movements that a lot of different communities can read themselves in. And there is an art and a craft to building these social movements. The environmental movement needs to bring together a bunch of different people if they want to fight climate change at the international level.

The third, which I think is the most ignored in America today, is the political party. The political party is the concrete manifestation of a bunch of people coming together to try to build a majority, in order to advance their vision. A recent book – Hollow Parties – went viral in political science circles because we have such a centralised management culture and such a weakened local chapter culture within political party structures. Now, the political party is just whoever the candidate is on TV.

With growing concerns about social disconnection, many commentators describe a “loneliness epidemic” or even a broader “crisis of belonging.” You’ve suggested, however, that this emphasis on belonging might actually be missing a deeper issue — what you call a “crisis of membership.” Could you explain what you mean by this deeper problem, and why you see membership as so vital in addressing these challenges?

This is what you could call ‘individualist communitarianism’: we're in such an individualist time that we process everything through an individualist lens, and therefore, even the alternative to hyper-individualism needs to be processed through an individualist lens. Of course, in Join or Die, we make a lot of arguments that joining a club is good for you as an individual. You have to start the conversation somewhere. But the idea of belonging could be defined as an individual feeling of being part of something, a feeling of being accepted into a larger world. We want a world where more people feel like they belong. But what we like about the phrase ‘membership’ is that it gets at the larger structure that includes the individual, but is also beyond it. So it is not just about the individual feeling in that person, even though it is one of the byproducts of membership.

Membership is the relationship between the person, the larger community, and the institutions. When you're a member of something, it's not just that you feel a part of it; you take responsibility for it. You are responsible for knowing its past and stewarding its present and co-creating its future. You are no longer a consumer or a client or a constituent of the broader world. You are a collaborator, a citizen, a caretaker of it. You need to actively participate in something to be a member of it, but it is also about what it needs to do for you. So the world needs to be reconstructed in a way that it opens itself up and invites participation.

There was a lot of writing in the mid-twentieth century about the fear that the world was moving in a direction that leaves the individual outside all of these big entities. They're all in a black box and we don't really know what’s going on; they control us, but we don't really know how they're made. But membership culture is about blurring the lines between the inside and the outside by inviting people to participate in the world. It also blurs political distinctions because, in one sense, I may sound like a conservative when I say it's about you taking responsibility for the world around you, but then I'm sounding like a leftist when I'm saying it's about you co-creating the world and reconstructing it into what you believe it should be.

In my work at the Centre for Democratic Business, I’ve been making more connections between business membership – in mutuals of one kind or another – and membership in voluntary associations.

Through a project we’re launching soon – Membership Nation – we’re bringing together membership organisations from across business, civil society, and politics to strengthen this culture and demonstrate how they are a vital part of civic revival and democratic renewal.

One important area to consider is ‘Who has the time for civic revival?’ How do you approach this question?

This is a huge part of the story. The materials that make up civil society are time, energy, and resources. When we’re saying that we want to embody things in civic life, that needs time. I have two feelings on this. One is that, for people who care about rejuvenating civic life, for people who care about civic development in their countries, the cause of free time, and stable time, is very important. And so the cause of stable work hours, the cause of the four-day working week, which is growing in popularity all across the world, the cause of more parental leave (so much of civic life was powered by one-income households where the other parent was often participating in civic life) are all important. Anything that can bring economic stability to people's lives will probably help civic life.

The second part of this, though, is that we don't want people just waiting for that before doing the work of rejuvenating civic life – because we know from history that people who were tremendously time-pressed, and in tremendously economically precarious situations, did some of the best social organising in American history. Great examples include the people who were part of the civil rights movement, the Montgomery bus boycott, the March on Washington. They were people from the most oppressed end of the economic structure. The people behind the United Farm Workers and the grape boycott under Cesar Chavez were migrant workers in the fields working over ten hours a day, six to seven days a week. They still found a way to organise, and the reason they found a way to organise was because they knew that organising was the only way to make things better.

One of the things my sister Rebecca Davis, who made the film Join or Die with me, and I have been saying on our tour is this phrase: What are you doing alone that you could be doing together? There are all these things that you're taking time to do alone, and with a little bit of upfront time to get a community set up, you can take that same hour where you're doing something alone and suddenly do it together, and that can start building community and solidarity. So if you are tired at the end of the day and just need a rest at the end of the day and just watch TV — there is a TV-watching club that was started in San Francisco that we heard about in the last year where people are just getting their rest in together. If you are so busy with childcare and you need to take your kids to the playground, we've heard of playground clubs where people are taking their kids to the playground and then meeting other parents and building solidarity among parents. We have heard of so many civic groups that have done a good job of having childcare and meeting other people's needs. The Rotary Club started at lunch because everyone needed to eat lunch anyway. We need to get creative in trying to find ways to fit this into people's lives already and make it a thing that makes time, not just a place where you have to find time.

Finally, your book – Dedicated: The Case for Commitment in an Age of Infinite Browsing – is built around the tension of ‘open options’ and the ‘counterculture of commitment’ as it plays out in contemporary society.

Can you explain the implications of these approaches and why you think regular commitment is so essential to reviving democratic life in the present?

As I was growing up, the advice that we always got from people who were older than us was: “Keep your options open.” It was like this creed for our generation. Pick the job that'll keep your options open. Don't get tied down to any relationship. Don't commit to this cause because it might shut down some options in the future. But then eventually we got to an age where we were the person in the future that we had been keeping our options open for, and we found out that it was not helping us. It was not the gift that we thought it was because we were in the exact same place where we started.

Meanwhile, there were people who decided to ignore this advice. I call them the “counterculture of commitment”. They're the people who decided to make a commitment to a particular thing, to enter into a relationship with a particular place, person, or cause, a particular craft or institution. They loved it enough to forego options for it. And it turns out that those people who had not kept their options open, who had made a commitment to a particular thing, were not only happier – they were the people that were making an impact on the world. I set out on this question of why we love ‘committers’ but we're following the advice of the ‘non-committers’ to keep our options open. How can we escape the ‘keeping-our-options-open’ trap?

What does it have to do with democracy? It comes back to that Hannah Arendt idea of “making and keeping promises” as key to public life – as a way to project a little bit of ordered creation onto an uncertain future.

We keep our options open out of fear of uncertainty, but it doesn’t work. And so the alternative is to face uncertainty through a different tool, which is community with others, what people might call ‘commitment’ or ‘solidarity’. Groups of people coming together and making and keeping promises to each other and to what they want to do together is what eventually co-creates the future. Whether it is fighting city hall, cleaning up the park, or stewarding some institution that you inherited, all of this requires that basic act of commitment.

At the beginning it is a brave act of making a commitment. But after a bunch of people make a commitment to each other, it starts having its own momentum because culture is formed by that commitment, and culture has a powerful magnetic force. Here are the three parts of the culture. One is that when you come together and make a commitment, you start developing things. External things are created, things change, community routines arise, traditions are formed. You do stuff out in the world, and that is really exciting. You get excited about making an impact and changing the world.

In the book, I talk about how so many young people when asked if they would die for a grand cause, respond, “Yes, I would die for a grand cause!” But then when asked, “Are you willing to go to a Tuesday night meeting every week next year for a grand cause?” That’s seen, in practice, as a much harder challenge.

The second is acculturation. Not only do you have external wins, but you also have internal wins. You learn how to work together with each other. You develop mastery of this culture that you're building together. You become really good at doing the thing that you do in that club, and you get really excited about growing as a person. It's not only that the club has an adventure; you have a heroic personal journey inside that adventure.

And then finally, the third is community. As you build all these external things, develop them as you all acculturate. If you're doing it together with other people, you all become friends, and you're excited about being in a community. That all adds up: development, acculturation, community into culture, which has a life of its own. But at the start you need that spark, and that initial spark is the brave act of making a commitment.

In the book, I talk about how so many young people, when asked if they would die for a grand cause, respond, “Yes, I would die for a grand cause!” But then when asked, “Are you willing to go to a Tuesday night meeting every week next year for a grand cause?” That’s seen, in practice, as a much harder challenge. That's the challenge to everyone: to not just be willing to die for a cause but to live for one – to tie ourselves down a bit for the sake of something bigger than ourselves that eventually becomes something much more freeing than we could ever imagine.

Pete Davis is a writer and civic advocate in Baltimore. He is the co-founder of the Democracy Policy Network, a policy group focused on raising up ideas that deepen democracy, the co-director of Join or Die, a documentary on community in America, and the author of Dedicated: The Case for Commitment in An Age of Infinite Browsing.