Worker co-operatives and employee ownership trusts (EOTs) are two different approaches to pursuing employee involvement in the ownership of a business. But are the two mutually exclusive – could EOTs be more co-operative?

A traditional workers co-operative has those who work in the business all involved in the ownership, typically on an equal basis. Members of staff will own a share (or shares) in the co-op, and often actively participate in decision making (though exactly how this is done may vary with the size and scale of the organisation).

By contrast, an EOT model (usually – but not exclusively – formed on the transfer of an existing business) involves the transfer of ownership of shares in a trading business to a trustee. The trustee holds those shares on behalf of all the employees for the time being, under the terms of a trust deed.

That trustee is often incorporated, and will therefore have a board of trustee directors, whose job it is to act in the shareholder role on behalf of the wider workforce. Staff do not directly own shares (though some may do so separately, through an employee share scheme). Involvement in decision making varies (sometimes wildly) from one EO business to another. The business continues to be run by the board of the operating company, with oversight from the trustee board.

There has been some suspicion of the EOT model in the co-op movement. Co-operators point to the fact that employees in an EOT-owned business do not, personally, own anything. They note that often selling shareholders continue to participate – actively – in the business, and that the board running the business may not change personnel. They see the trust model as insufficiently democratic, and failing to change a typically hierarchical set of relationships between managers and employees.

In our experience, this is not wholly fair because the models achieve employee ownership in different ways (though criticism on levels of engagement is justified in some cases, and practice varies widely). But it all misses a more important point – which is that there is no blueprint for how an EOT is constructed, and the model as it has developed so far is an emerging one, with ongoing debate about what constitutes good practice. Which in turn raises the question that co-operators should ask – is it possible to make an EOT truly co-operative in nature? The answer is “yes”.

There is no restriction in law as to the nature of the trustee body in an EOT; it can be an individual (or individuals) or, as we noted above, a corporate body. The only restrictions in law are that:

Both of these requirements were introduced in the October 2024 Budget.

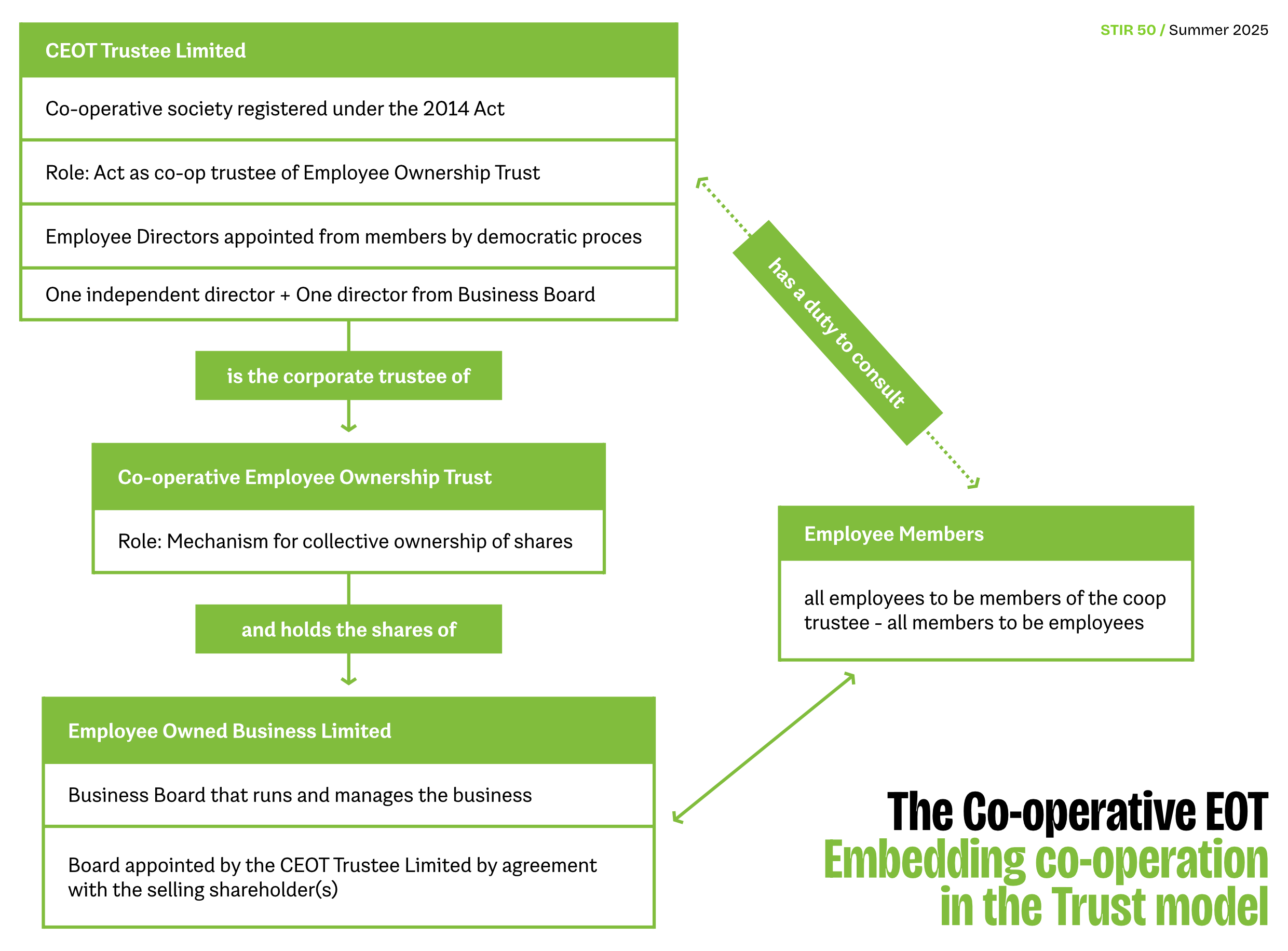

There is, therefore, nothing to prevent that trustee body being registered as a co-operative, and we have been exploring an approach where the corporate trustee would be registered as a co-operative society under the Co-operatives and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014.

In this model, the employees in the business would all be entitled to become members of the trustee co-op, for no or nominal consideration; the only members of the trustee co-op would be the employees. They would elect representatives to the co-op trustee board to act as employee trustee directors, alongside an independent trustee director (to give an independent perspective) and a representative (or possibly more than one) from the main “business” board. In effect this achieves what is a best practice model for many EOTs: a paritarian trustee board, where managers and employees views are equally taken into account in trustee decisions. But instead of relying on the trading company to arrange the employee trustee director appointments, as often happens, they would be made in accordance with a procedure built into the governance structure, one based on co-operative principles. This democratic election process can be written in the trust deed, but that would not, on our understanding, be sufficient to meet co-operative governance standards. Employees would cease to be members of the co-op trustee if they ceased to be employed by the business; they would have oversight of the business through the role of the trustee body as shareholder, as follows:

The trustee body and the business (which would have a constitution upholding co-operative principles) together would form a co-operative business entity.

European countries without trust law, such as Denmark, are trying to reproduce the EOT model. Interestingly, they are considering co-operative ownership of the entity equivalent to the EOT as the way to protect the employee ownership purpose of that entity.

We have taken informal soundings from specialists working with EOTs, and from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in its capacity as the registering body for co-operative societies. These advisors have confirmed that, in their view, there is no impediment to using a co-op society as the corporate trustee.

The FCA has said that, as a matter of policy, it would support the use of a co-op society in this role. They were prepared to agree with our view that active involvement in the business as a shareholder could constitute undertaking a “business, industry or trade” for the purposes of the 2014 legislation. We discussed in some detail the question of whether such a trustee body would meet the ‘bona fide co-operative’ test in the Act, and the FCA is of the view that it would be important that all the employees were able to become members of the co-op; the clear link between membership and employment helps build the argument that members are actively participating in the economic life of the business.

There remain issues of detail to be finalised. For example, this change introduces some governance complications that are avoided with the popular EOT trustee model of a company limited by guarantee, where its directors are also its members, and so only one group of individuals makes all decisions relating to the trustee and EOT, either as directors or members. The FCA has said they would welcome the submission of a set of proposed model rules for such a society for their consideration. It will clearly be important that there is consistency between the rules of the co-op trustee and, for example, the trust deed which creates the EOT, but we see no reason why these issues cannot be overcome.

A similar ‘co-operative’ outcome can and has been achieved in a couple of test cases, by using a company limited by guarantee as the trustee company, with employees as members of that company. But FCA registration of the trustee would remove any uncertainty over the trustee’s status as a co-operative.

This aspiration to make an EOT-owned business more distinctive in its governance is supported by other changes in the law, also introduced in the October 2024 Budget. As well as being independent from the sellers and set up in the UK, those changes make clear that there is an expectation that the trustee will also:

These Budget changes ensure more best practice is reflected in EOT legislation and therefore EOT structures. They reflect the need for strong and robust governance by the trustee, before and after transfer. In our view, the successful embedding of a genuinely co-operative approach into an EOT, as proposed above, without compromising other aspects of trustee governance, would make EOTs acceptable to co-operators.

David Alcock is a Partner and head of Social Business at Anthony Collins Solicitors LLP, where he leads on the firm’s work with co-operatives and on employee ownership.

Graeme Nuttall is a Visiting Fellow at Kellogg College. He is a former UK Government Employee Ownership adviser and works internationally on employee ownership.